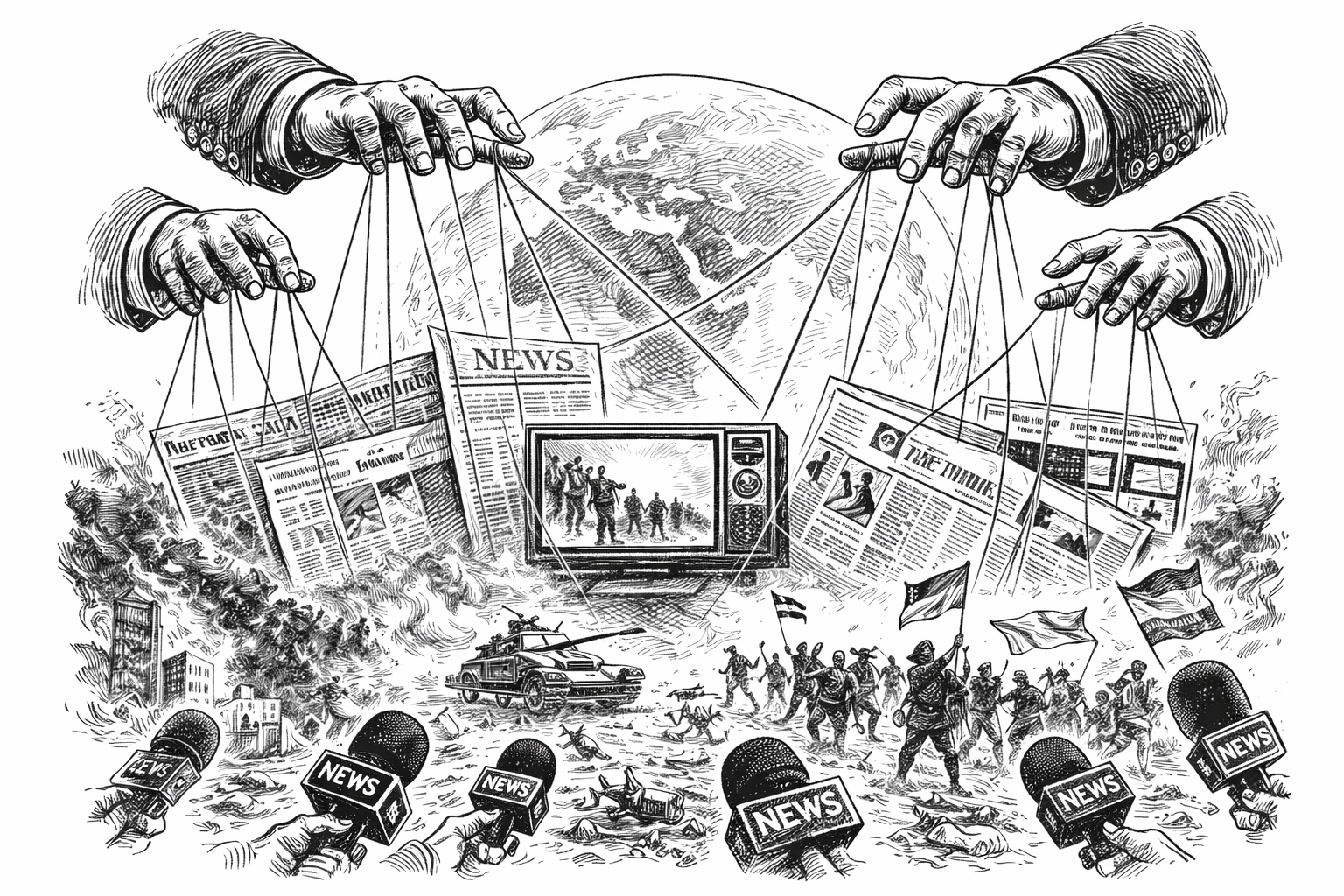

Spend enough time following global politics and a pattern begins to surface. The same event — a missile strike, a border skirmish, a diplomatic walkout — appears in the news, yet the meaning of what you have just read depends less on the facts than on where you encountered them. One version frames the act as deterrence, another as provocation, a third as tragic inevitability. None of these accounts is entirely false. But none is complete either. What differs is not reality itself, but the lens through which it is presented, and over time that lens becomes more influential than the event it claims to describe.

Modern media bias rarely announces itself. It does not resemble propaganda posters or overt slogans. Instead, it operates through framing decisions that appear technical and defensible: where the story begins, which historical reference point is treated as relevant, whether an action is described as escalation or response, whether agency is named directly or diffused into abstract phrasing. A civilian “is killed” in one report; civilians “die” in another. A strike is “retaliatory” here, “unprovoked” there. These are not grammatical quirks. They are narrative choices, and they quietly instruct the reader on how to feel before the reader realises a judgement is being formed.

Consider how the same conflict can be portrayed as a struggle for security in one part of the world and as aggression in another, depending on the political alignment of the actors involved. Consider how sanctions are framed as moral instruments when imposed by some states and as economic warfare when imposed by others. Or how civilian suffering becomes a rallying cry in one theatre and a regrettable side note in another. These inconsistencies are often explained away as differences in editorial culture or audience expectations, but beneath them lies a simpler logic: interests shape attention, and attention shapes morality.

This is why the old principle of international relations continues to hold its ground: there are no permanent friends, only permanent interests. Governments acknowledge this openly. Media ecosystems, particularly global ones, reflect it more subtly. Access to officials, reliance on sources, national perspective, and the assumptions of a primary audience all exert pressure on how stories are framed. Hypocrisy, in this context, is not a deviation from the system. It is a predictable outcome of it. The same behaviour can be condemned, contextualised, or ignored altogether depending on who benefits from which interpretation.

Outrage, too, follows patterns. Some humanitarian crises dominate the news cycle for weeks, accompanied by panels, think pieces, and moral urgency. Others, no less severe, pass with minimal attention. The difference is rarely scale alone. It is strategic relevance. It is narrative convenience. It is whether the suffering fits cleanly into an existing story that audiences already understand. This does not make the suffering less real. It determines whether it will be remembered, debated, or quietly archived.

For readers who notice these patterns, the news begins to feel less like a record of events and more like a map of incentives. The question shifts from “what happened?” to “why is this being framed this way, now?” That shift is uncomfortable, because it removes the clarity of simple moral positioning. It forces the reader to sit with ambiguity, to acknowledge that multiple truths can coexist, and that empathy and analysis do not always point in the same direction.

Geopolitics, stripped of its language, is not a contest of good versus evil. It is a system — repetitive, interest-driven, constrained by power and consequence. Understanding that system does not make it humane. But it makes it intelligible. And in a world where narratives often arrive fully formed before facts have settled, the ability to recognise how stories are constructed becomes as important as the stories themselves.