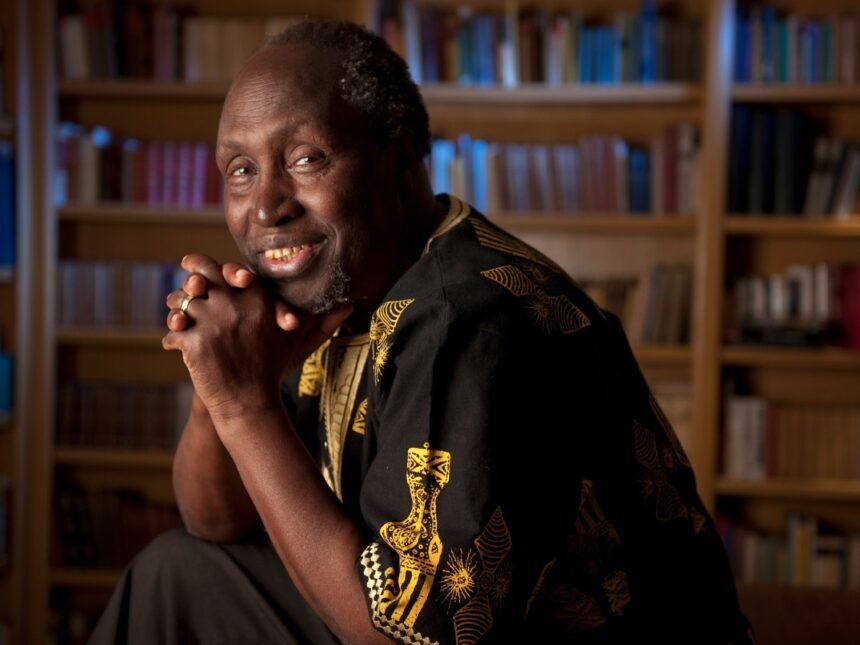

Ngugi wa Thiong’o cherished to bounce. He cherished it greater than the rest – much more than writing. Properly into his 80s, his physique slowed by more and more disabling kidney failure, Ngugi would rise up and begin dancing merely on the considered music, by no means thoughts the sound of it. Rhythm flowed by way of his toes the way in which phrases flowed by way of his arms and onto the web page.

It’s how I’ll at all times keep in mind Ngugi – dancing. He handed away on Could 28 on the age of 87, abandoning not solely a Nobel-worthy literary legacy however a mix of deeply revolutionary craft and piercingly authentic criticism that joyfully calls on all of us to do higher and push more durable – as writers, activists, lecturers and folks – in opposition to the colonial foundations that maintain all our societies. As for me, he pushed me to go far deeper up river to Kakuma refugee camp, the place the free affiliation of so many vernacular tongues and cultures made doable the liberty to assume and communicate “from the center” – one thing he would at all times describe as writing’s best reward.

Ngugi had lengthy been a constitution member of the African literary canon and a perennial Nobel favorite by the point I first met him in 2005. Attending to know him, it shortly grew to become clear to me that his writing was inseparable from his instructing, which in flip was umbilically tied to his political commitments and lengthy service as one in all Africa’s most formidable public intellectuals.

Ngugi’s cheerfulness and indefatigable smile and snicker hid a deep-seated anger, reflecting the scars of violence on his physique and soul as a toddler, younger man and grownup victimised by successive and deeply intertwined techniques of criminalised rule.

The homicide of his deaf brother, killed by the British as a result of he didn’t hear and obey troopers’ orders to cease at a checkpoint, and the Mau Mau revolt that divided his different brothers on reverse sides of the colonial order through the ultimate decade of British rule, imbued in him the foundational actuality of violence and divisiveness as the dual engines of everlasting coloniality even after independence formally severed the connection to the metropole.

Greater than half a century after these occasions, nothing would arouse Ngugi’s animated ire greater than citing in a dialogue the transitional second from British to Kenyan rule, and the truth that colonialism didn’t go away with the British, however reasonably dug in and reenforced itself with Kenya’s new, Kenyan rulers.

As he grew to become a author and playwright, Ngugi additionally grew to become a militant, one dedicated to utilizing language to reconnect the complicated African identities – native, tribal, nationwide and cosmopolitan – that the “cultural bomb” of British rule had “annihilated” over the earlier seven many years.

After his first play, The Black Hermit, premiered in Kampala in 1962, he was shortly declared a voice who “speaks for the Continent”. Two years later, Weep Not Baby, his first novel and the primary English-language novel by an East African author, got here out.

As he rose to prominence, Ngugi determined to surrender the English language and begin writing in his native Gikuyu.

The (re)flip to his native tongue radically altered the trajectory not simply of his profession, however of his life, as the flexibility of his clear-eyed critique of postcolonial rule to achieve his compatriots in their very own language (reasonably than English or the nationwide language of Swahili) was an excessive amount of for Kenya’s new rulers to tolerate, and so he was imprisoned for a 12 months with out trial in 1977.

What Ngugi had realised when he started writing in Gikuyu, and much more so in jail, was the truth of neocolonialism as the first mechanism of postcolonial rule. This wasn’t the usual “neocolonialism” that anti- and post-colonial activists used to explain the continuing energy of former colonial rulers by different means after formal independence, however reasonably the prepared adoption of colonial applied sciences and discourses of rule by newly unbiased leaders, lots of whom – like Jomo Kenyatta, Ngugi appreciated to level out – themselves suffered imprisonment and torture beneath the British rule.

Thus, true decolonisation may solely happen when individuals’s minds have been free of overseas management, which required first and maybe foremost the liberty to write down in a single’s native language.

Though not often acknowledged, Ngugi’s idea of neocolonialism, which owed a lot, he’d repeatedly clarify, to the writings of Kwame Nkrumah and different African anti-colonial intellectuals-turned-political leaders, anticipated the rise of the now ubiquitous “decolonial” and “Indigenous” turns within the academy and progressive cultural manufacturing by virtually a technology.

Certainly, Ngugi has lengthy been positioned along with Edward Stated, Homi Bhabha and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak because the founding technology of postcolonial thought and criticism. However he and Stated, whom he’d incessantly talk about as a brother-in-arms and fellow admirer of Polish-British author Joseph Conrad, shared an analogous all-encompassing deal with language, at the same time as Stated wrote his prose principally in English reasonably than Arabic.

For Stated and Ngugi, colonialism had not but handed, however was very a lot nonetheless an ongoing, viscerally and violently lived actuality – for the previous by way of the ever extra violent and in the end annihilatory settler colonialism, for the latter by way of the violence of successive governments.

Ngugi noticed his hyperlink with Stated of their frequent expertise rising up beneath British rule. As he defined in his afterword to a lately printed anthology of Egyptian jail writings since 2011, “The efficiency of authority was central to the colonial tradition of silence and concern,” and disrupting that authority and ending the silence may solely come first by way of language.

For Stated, the swirl of Arabic and English in his thoughts since childhood created what he known as a “primal instability”, one which could possibly be calmed totally when he was in Palestine, which he returned to a number of instances within the final decade of his life. For Ngugi, at the same time as Gikuyu enabled him to “think about one other world, a flight to freedom, like a chicken you see from the [prison] window,” he couldn’t make a ultimate return house in his final years.

Nonetheless, from his house in Orange County, California in the USA, he would by no means tire of urging college students and youthful colleagues to “write dangerously”, to make use of language to withstand no matter oppressive order by which they discovered themselves. The chicken would at all times take flight, he would say, for those who may write with out concern.

The views expressed on this article are the creator’s personal and don’t essentially mirror Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.